What the Fight Over Scooters Has in Common With the 19th-Century Battle Over Bicycles

The two-wheelers revolutionized personal transport—and led to surprising societal changes

:focal(271x830:272x831)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/1c/dd1cfbfe-3d57-43c2-b245-bb8b36f22a7e/dec2019_d10_prologue.jpg)

It was a hot summer day in Hoboken, New Jersey, and the streets were buzzing with electric scooters.

Two months earlier, the companies Lime and Ojo had unleashed 300 of the devices on the town. You could pay $1 or more to unlock a scooter with your mobile phone, then 10 to 29 cents per minute to ride it, leaving it parked on the sidewalk or docking station when you were done. By July, you couldn’t go a block without seeing riders zip by: young women in sundresses, a couple heading downtown to catch a train, two men in athletic wear, squash rackets slung over their shoulders. “You gotta hold on tight,” one rider, a young man coiffed scruffily and wearing sunglasses, advised me, “because these things take off when you hit the throttle. Sixteen miles an hour! It’ll throw you!”

E-scooters are part of a wave of “micromobility” companies that have arrived, seemingly overnight, in U.S. cities, plopping down thousands of electric bikes and scooters. Fans swear by them, arguing that the scooters let them take fewer car rides, saving money and reducing carbon dioxide emissions, while opening up parts of the city they might otherwise never go to. Plus, “they’re just so much fun,” one Hoboken woman gushed.

“Micromobility is solving the last-mile problem,” of traveling short distances when public transit and cabs aren’t convenient, says Euwyn Poon, president and co-founder of Spin, a division of Ford that offers dockless electric scooters.

But the kudzu-like growth of scooters has also tangled urban life. City officials complain the firms don’t manage the behavior of riders, who are generally not supposed to ride on sidewalks but frequently do, enraging pedestrians (and sometimes plowing into them). Riders are also supposed to park scooters neatly upright, but when some are inevitably strewn about on sidewalks, they become an obstacle. And on America’s badly maintained roads, fast-moving scooters aren’t terribly stable, and the companies don’t provide helmets with each ride. Hitting a bump or pothole can send riders flying, knocking out teeth or even causing traumatic head injuries.

Furious citizens are now vandalizing the devices nationwide: Behold the Instagram feed “Bird Graveyard,” devoted to images of Bird scooters and their kin poking mournfully out of riverbeds, where they’ve been hurled, or buried handlebar-deep in sand. “Those things are a straight-up public menace,” fumed one Hoboken resident on Twitter. Some city politicians are trying to ban the scooters altogether.

It’s a messy rollout, pun intended. The last time we saw an intense debate like this over a curious new form of personal transportation that suddenly descended on cities and angered pedestrians was a century ago, and the “micromobility” in question was the bicycle.

* * *

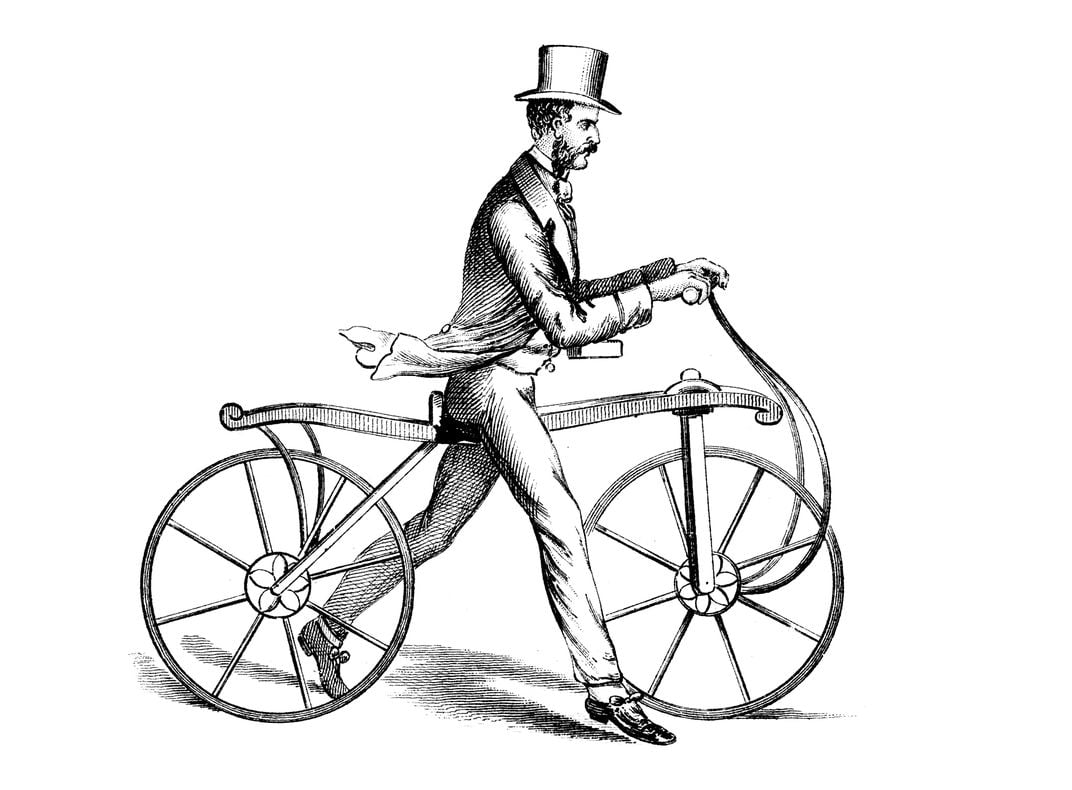

It took inventors about 70 years to perfect the bicycle. An ur-version was built in the 1810s by the German inventor Karl von Drais, and it was just two wheels on a frame. You scooted along by pushing it, Flintstones-style, with your feet. “On a plain, even after a heavy rain, it will go 6 to 7 miles an hour, which is as swift as a courier,” Drais boasted.

By the 1870s, entrepreneurs were putting pedals on the front wheel, creating the “velocipede” (the Latin roots for “fast foot”). Since a bigger wheel went faster, inventors built front wheels as huge as five feet tall, stabilized by a tiny back wheel—a “penny farthing,” as the cycle was known. Riding was mostly a sport of well-off young men, and riders exulted at the dual feelings of speed and height. “From the saddle we perceive things which are hidden from them who only walk upon the earth,” one Connecticut rider boasted in 1882. “We dash across the plain with a wild sense of freedom and power which no one ever knows until he rides the magic steed.”

From the very beginning, though, riders were also mocked as fops pursuing a ludicrous pastime. Pedestrians back then were the prime users of roads and sidewalks, so cycles seemed like dangerous interlopers. A Baltimore newspaper called the bicycle “a curious two-wheeled device...which is propelled by jackasses instead of horses.” One New Haven, Connecticut, newspaper editorial even encouraged people to “seize, break, destroy, or convert to their own use as good prize, all such machines found running on the sidewalks.” As long ago as 1819, a New York man wrote a letter to a newspaper complaining that you “cannot enjoy a walk in the evening, without the danger of being run over by some of these new-created animals.”

In truth, the bikes were arguably more dangerous to the riders themselves. Hit a bump and you might find yourself “taking a header”—a coinage of the time—by flying over the high front wheel. “Plenty of people died riding penny farthings,” notes Michael Hutchinson, a bike racer and author of Re:Cyclists, a history of cycling.

The bicycle didn’t truly reach the mainstream until engineers began selling the “safety” bike in the 1890s. With inflatable tires, it offered a gentler, less bone-shaking ride, and the chain propelling the back wheel left the front free for steering. Now this was something anyone could ride—and anyone did, as dozens of bike firms flooded the market. The bicycle craze was born.

“People were buying a new bike every year, they wanted to have the latest model—it was like the iPhone today,” says Robert Turpin, a historian at Lees-McRae College and author of First Taste of Freedom, a study of early bicycle marketing. Bicycle ads flourished and Americans devoured bicycling magazines. “There were daily bicycling print publications,” marvels Sue Macy, author of Wheels of Change.

Cyclists took to city parks, or fled crowded urban areas. Some challenged themselves to ride 100 miles in a day. Clubs formed for outings and races, and long-disused roadhouses were rehabilitated to service cyclists on long journeys. “Everything is bicycle,” as the author Stephen Crane quipped.

To many, cycling embodied the very spirit of American freedom and equality. “As a social revolutioniser it has never had an equal,” Scientific American observed in 1896. “It has put the human race on wheels, and has thus changed many of the most ordinary processes and methods of social life. It is the great leveller.” By 1900, there were more than 1.25 million cyclists in the United States.

Conflict ensued. Horses, in particular, would bolt or panic at the approach of a madly pedaling cyclist. Some livery drivers fought back by deliberately running over cyclists, or spitting tobacco at them. Pedestrians got in fistfights with cyclists who collided with them, or even pushed them into the path of oncoming trolley cars. “With park guards unfriendly, and policemen openly hostile,” the New York Sun noted, cyclists had plenty of opposition. New York’s city council banned bikes from public parks; in retaliation, the founder of the country’s biggest bicycle firm encouraged three cyclists to deliberately break the law so he could mount a court challenge.

Initially, doctors fretted that cycling would cause health problems, such as “bicycle face,” a rictus supposedly caused by holding your mouth in grimace and your eyes wide open. “Once fixed upon the countenance, it can never be removed,” a journalist soberly warned. Or beware “kyphosis bicyclistarum,” a permanent hunching of the back, acquired from bending over the handlebars to go faster. Soon, though, these quack diagnoses faded; it was obvious that cycling improved health. Indeed, doctors advised cycling to help exercise the increasingly sedentary, desk-bound office workers of the new industrial economy.

* * *

Another big social change the bicycle wrought was in the lives of middle-class American women. In the Victorian period up until then, geographically speaking, “their lives were very circumscribed—they were supposed to stay home and take care of the family,” notes Margaret Guroff, author of The Mechanical Horse: How the Bicycle Reshaped American Life. Traveling far under their own steam wasn’t easy for young middle-class women, given that they wore heavy petticoats and corsets.

Riding a bicycle felt like a burst of independence. “Finally you could go where you wanted, on your own,” Macy says. “When you were riding a cycle your mother didn’t know where you were!” Young women could meet potential paramours on the road, instead of having their parents size them up in their living room. Soon women were 30 percent of all cyclists, using the newfangled technology to visit friends and travel the countryside. It was empowering. “Cycling is fast bringing about this change of feelings regarding women and her capabilities,” the Minneapolis Tribune wrote. “A woman awheel is an independent creature, free to go where she will.”

It even changed clothing. Feminists had long promoted the “rational dress” movement, arguing that women should be allowed to wear “bloomers,” blousy pants; but it had never caught on. Bicycles, though, made the prospect of wearing “bifurcated raiment” newly practical. Skirts got caught in wheels. By the 1890s, a women in bloomers on a bicycle was an increasingly common sight.

“I’ll tell you what I think of bicycling,” the suffragist Susan B. Anthony said in 1896. “I think it has done more to emancipate woman than any one thing in the world.”

* * *

Electric scooters are unlikely to pack such a powerful social punch. But proponents argue that they could lower emissions in cities—if they become ubiquitous and residents use them both to supplant trips in cars and to augment spotty public transit. “People are looking for alternatives,” says Lime executive Adam Kovacevich.

City officials can be dubious, though, given the chaos that has accompanied the arrival of scooters. For example, Nashville allowed the firms to set up shop in 2018, but a year later, after seeing scooters strewn about and accidents, Mayor David Briley “believes that scooters have been a failed experiment,” a City Hall spokesman told me in an email. Briley proposed banning them; the city council voted to halve the number instead—from 4,000 to 2,000—and asked the scooter firms to manage their customers better. Atlanta banned them at night. Public opinion seems bimodal: People either cherish or despise them. A few riders told me they started as fans, only to change their minds after experiencing terrible accidents—including one woman I emailed who spent months recovering from brain damage.

Are these just growing pains, like those that accompanied the rise of the bicycle? Possibly: It took years for protocols and regulations on bike-riding to emerge—though one difference today is the on-demand scooters are deployed not by individual owners, but by huge, high-tech firms seeking to blanket the city and grow rapidly. When people actually own their scooters, they worry about carefully storing and riding them. On-demand users don’t, and the firms seem willing to tolerate the resulting equipment damage. As Carlton Reid—author of Roads Were Not Built for Cars—points out, the fight for bicyclists’ rights was a genuinely grass-roots movement. “The difference now is the companies are doing this—it’s Uber, it’s these companies that own this, the Limes and the Birds,” he notes. On the other hand, having scooters distributed all around town is part of what helps them become widely used, rapidly.

Some argue that cars are the problem: We give them so much space there’s little left. Given the emissions of automobiles, and how routinely cars kill people, they shouldn’t enjoy such largess, argues Marco Conner, deputy director of Transportation Alternatives, a think tank in New York City. He’s in favor of scooters, and thinks cities should build more bike lanes—to give scooters a non-sidewalk place to ride safely—and reallocate one curbside car-parking space per block for micromobility parking and charging. Scooters do reduce car use, he argues: When Portland, Oregon, studied how residents used the scooters, it found 34 percent of the trips replaced a car trip.

“We’re accommodating the movement and storage of multiton lethal vehicles,” Conner says. With the rise of micromobility, the fight is on again to see what type of wheels will rule the streets.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Clive_Thompson_photo_credit_is_Tom_Igoe.jpg)