As with most things that permeate our lives, we notice traffic mainly by its absence. When communities across the country went into lockdown mode during the early phases of the coronavirus pandemic, driving dropped by nearly half.

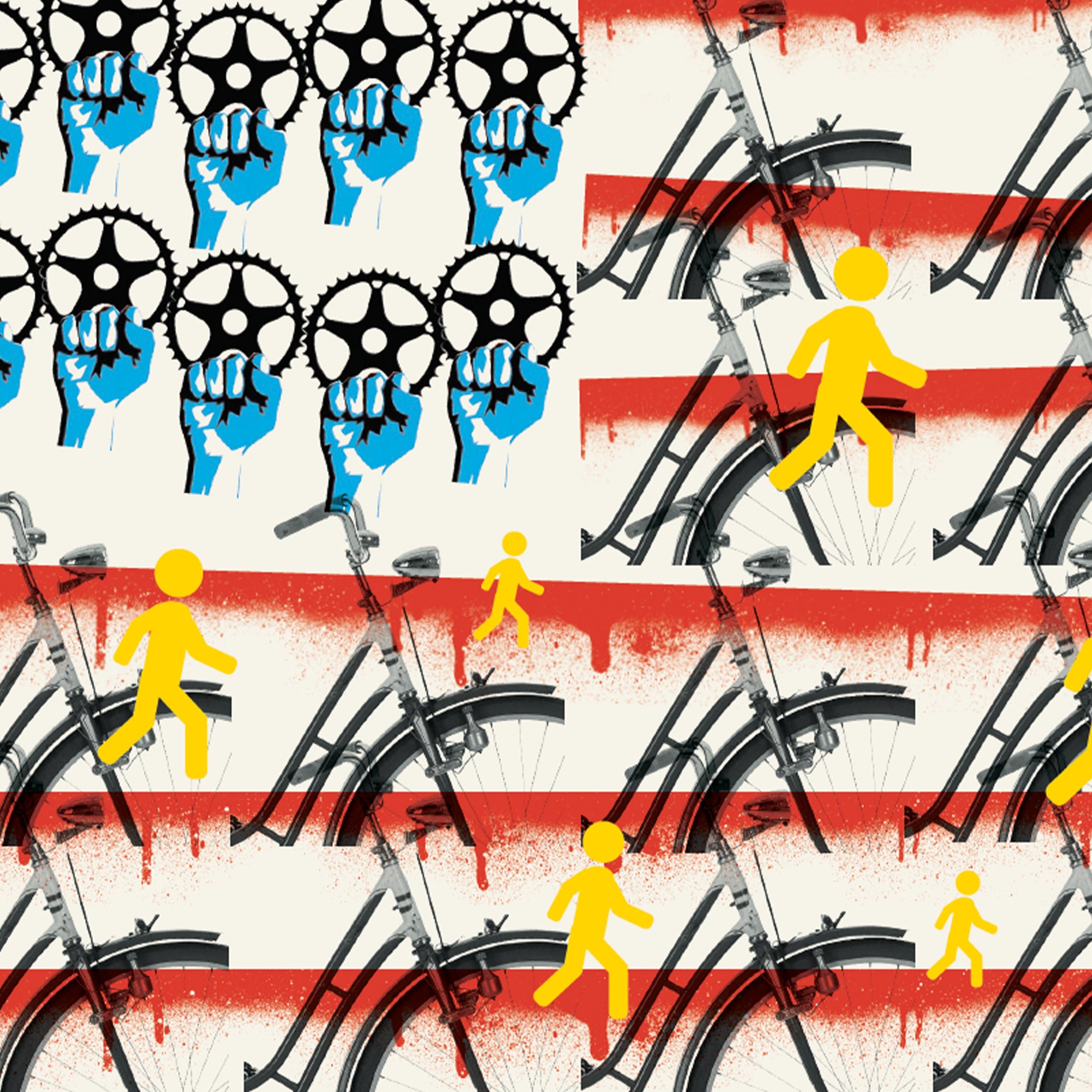

We still went outside: to run, to ride bikes, to walk the dog, to see blue skies and green things, to stay sane. And when we did, we saw yawning expanses of empty pavement. For decades in American cities, anyone not in or on a motor vehicle of some sort has been relegated to cramped sidewalks or constricted bike lanes, and pressed into pocket parks. Scrabbling along at the margins of suddenly empty roadways, we noticed the sheer unfairness of it all.

To their credit, many cities moved quickly, closing off streets to cars—and opening them by the dozens to non-vehicular use. Few did it faster or more aggressively than Oakland, California, which converted 74 miles under its Slow Streets program, barring motor-vehicle traffic—except for local access—to encourage exercise and play.

The result, there and in other cities, was something Americans usually experience only while traveling abroad: stress-free walking and cycling, on streets where cars are courteous guests rather than dangerous dictators. In some spots, entire blocks were converted into plazas for open-air dining.

It’s callous to call a global pandemic an opportunity, but the crisis has altered our view of public spaces in ways no other event could. In Denver, which closed several streets to through traffic, that wouldn’t have happened without a catalyst. “If we had tried to roll this out pre-pandemic, we would have been met with opposition,” says Eulois Cleckley, executive director of the city’s Department of Transportation and Infrastructure. “But the situation people were placed in changed their perspective overnight.”

“Streets are a form of technology,” says Kevin Krizek, a professor of transport at the University of Colorado. “They could and should evolve with time.”

We can make cities friendlier and safer for walking and cycling—cleaner, greener, quieter, and more livable. But we’ve wanted that for years, even as we failed to make it happen. How do we do it differently this time?

It won’t be easy. For decades, Americans have made driving our preferred mode of transportation. Since 2018, federal spending for cycling and pedestrian infrastructure has topped $850 million per year, according to the Federal Highway Administration. That sounds like a lot. But federal funding for roads in 2020 amounted to $47 billion.

Meanwhile, even before COVID-19 struck, public transit ($15 billion in spending last year) was in a tough spot as it competed with car-hailing companies and lost ridership, which in turn forced fares higher to make up the shortfall. Now it’s in survival mode; the Denver area’s RTD transit agency faces a projected $1.3 billion gap by 2026, while the East Bay’s AC Transit may be forced to cut almost a third of its bus routes. Rebuilding will take time and money. “Transit is a complicated solution,” Krizek says. “It’s expensive, long-term, and hard to convince people to take advantage of.”

Transportation issues negatively affect people of color far more than white communities. Interstate highways that fueled sprawl and white flight were built on roads that cut through, or over, Black, Latino, and immigrant neighborhoods. Redlining—denying minorities essential services like mortgages—along with other discriminatory practices, prevented people of color from leaving cities even as pollution increased and grocery stores and other neighborhood businesses closed.

The inescapable result is that the transportation systems we’ve built are hopelessly flawed and deeply discriminatory, and cars are still the easiest, most flexible choice for most. Without them—or with vast reductions in use—how will people commute or run errands in bad weather, sometimes carrying large, heavy loads, with family members ranging from infants to the elderly, on trips ranging from half a mile to dozens of miles?

There has been justified criticism of hasty street closures by some transportation departments, but the truth is we must move quickly. “We’ve had a dramatic shake-up in travel behavior,” Krizek says of the pandemic, but that may be temporary. In a new study, Krizek and lead author Meredith Glaser found that of 30 large U.S. cities that instituted Slow Streets–like programs, only five were moving to make the changes permanent at the time of their research. Most troubling, by late June, vehicle traffic nationwide rebounded almost to pre-pandemic levels, while transit ridership languished at record lows.

Cycling and walking aren’t do-it-all solutions for cities. But as transit falters, they provide a vital safety valve. They’re easy and relatively affordable—basically free, in the case of walking. They rely on existing, proven systems, while e-bikes and other new technologies are well-suited to novice riders.

And the infrastructure is cheap. Even comparatively expensive approaches like protected bike lanes are a bargain at between $20,000 and $100,000 per mile when measured against the $1 million it costs to build that much car lane.

What does the city of the future look like? It’s easy to point to someplace like Utrecht, in the Netherlands, with its plentiful pedestrian pathways and, at the city’s main train station, gleaming new 12,500-spot bicycle garage (the world’s largest). Or even London, where cycling could increase tenfold in the years ahead, and walking fivefold. In 2018, the city announced a plan to build biking and walking infrastructure; Mayor Sadiq Khan recently expanded the scope and accelerated the timeline, while Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that the central government would commit more than $2.7 billion to create a “new golden age of cycling” in the UK.

But Utrecht, along with Copenhagen, has been building for decades, while London has only begun. Perhaps the best example of a fast, successful, recent transition is Paris, which started just five years ago. Under Plan Vélo, Mayor Anne Hidalgo installed bike lanes and slashed car access and parking. In response, Parisians have tripled their trips by bike on some roads. Hidalgo calls the next phase the 15-minute city, where residents can get everything they need or want in that time frame by bike or on foot.

Of course, those solutions work well for dense, compact Paris. But what about sprawling U.S. cities? Many of them lack efficient public-transit systems. Still, approximately 60 percent of all vehicle trips in the U.S. are less than six miles, according to the Department of Energy. That’s a suitable distance for a bike, especially one that’s e-powered.

For walking, cycling, and so-called micromobility options like scooters to really function as everyday transportation choices for more than just hardcore commuters, Krizek says, there has to be a safe route from anywhere in a city to anywhere else. In its next phase, Paris will add some kind of bike lane to every street by 2024.

U.S. cities are following suit. Last year, Oakland released its first new infrastructure plan for bikes in 12 years, with an emphasis on equity, so that all residents have access to safe, low-stress bike networks. In July, Denver unveiled its new Complete Streets design guidelines, explicitly noting for the first time in the city’s history that it intends to give pedestrians, cyclists, and micromobility users the same safe street conditions that motor vehicles enjoy.

When we build these kinds of cities, what will they be like? Quieter, calmer, and cleaner, for starters. As traffic dropped during the pandemic, air quality improved dramatically, with notorious problem areas like Los Angeles registering a 51 percent reduction in sooty, lung-damaging PM2.5 pollutants.

Such cities are also safer. Twenty-nine cyclists and 124 pedestrians died in New York City in 2019, while walk- and bike-friendly cities like Oslo and Helsinki recorded zero fatalities.

They’re saner, too. Robin Mazumder, a doctoral student in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, studies the effects of urban environments on mental health. Cities, in particular downtown areas, where concrete dominates, are especially bad for us, linked to increased stress and higher rates of mental health problems.

Healthy cities are vibrant cities, with ample green space that absorbs heat and boosts emotional wellness. They also have public art, which promotes wonder, boosts civic pride, and creates a sense of belonging for everyone, especially marginalized communities. A functional example? Oakland’s 90th Avenue bike lane, painted to evoke the city’s famous, ornately decorated scraper bikes.

These cities are also economically stronger: lost productivity caused by traffic congestion costs $305 billion a year in the U.S., according to a 2018 study from data-analytics firm Inrix. And contrary to merchant fears, walk- and bike-friendly districts often increase revenue to businesses, even as car parking is reduced. It turns out that those dining plazas, protected bike lanes, and spacious sidewalks are good for the bottom line.

The pandemic has been many things. It’s an X-ray, showing how the disease of racism threatens our society. It’s a reckoning, a once-in-a-century event forcing us to acknowledge dysfunction and providing fresh urgency to confront and solve it. And, as the novelist Arundhati Roy wrote in The Financial Times, it’s a portal, a gateway between worlds. “Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew,” she wrote.

But here’s the catch: it wasn’t a portal we chose to walk through. The pandemic made that choice for us. What matters now is what we build on the other side.